How “Chicken Gun Testing” Became Vital for Aviation Safety

Aircraft safety is a top priority in the aviation industry, and one unconventional yet critical tool in ensuring this safety is the “chicken gun.” This specialized device is used to test aircraft components by simulating bird strikes, a common hazard faced by planes during flight.

The chicken gun fires bird carcasses at high speeds to assess the structural resilience of key parts like windshields, canopies, and jet engines. While the name might sound whimsical, the science behind it is serious and has saved countless lives.

The origins of the chicken gun date back to 1942 when the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Administration, in partnership with Westinghouse Electric, developed the first device capable of launching birds at aircraft components at speeds up to 400 mph.

This innovation marked a turning point in aviation safety by revealing vulnerabilities in aircraft windshields. Similar devices were later developed independently by other nations, including the UK’s Royal Aircraft Establishment in the 1960s and Canada’s National Research Council in 1968. These early efforts laid the foundation for modern bird strike testing.

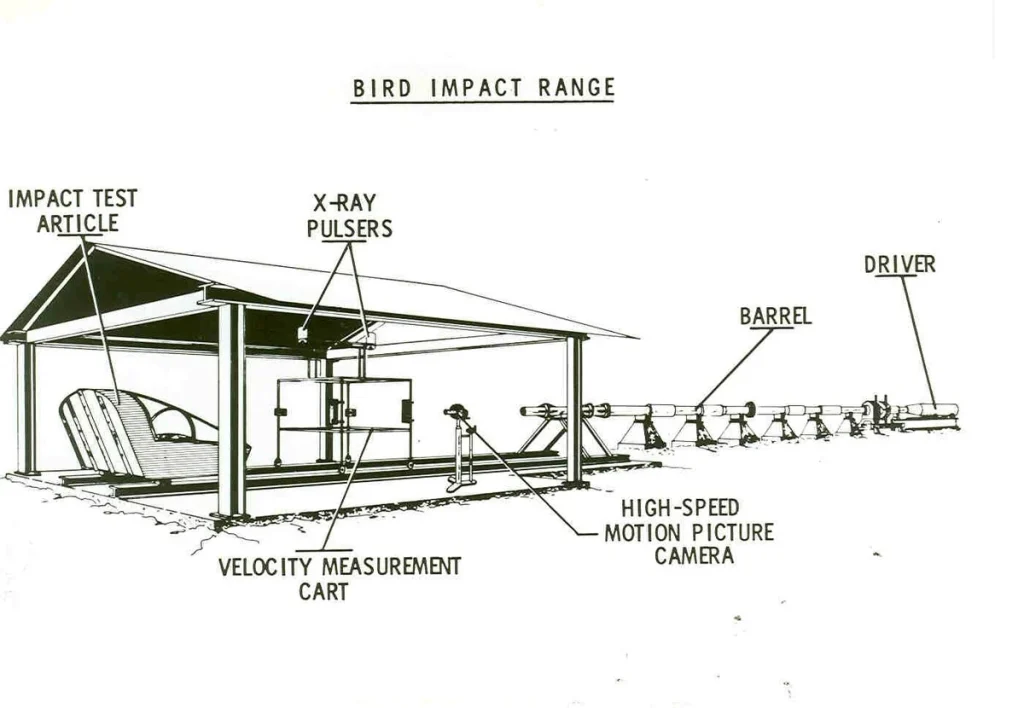

Today, chicken guns are essential for certifying aircraft. Testing involves securely mounting components and firing unfrozen birds at velocities replicating real-world conditions. This ensures that aircraft can withstand bird strikes without catastrophic failure.

One notable facility is the Ballistic Range S-3 at Arnold Engineering Development Complex in Tennessee, operational since 1972. This range has been pivotal in testing military aircraft canopies, including those on the A-10 and F-16 fighter jets. General Electric also uses similar methods to test the durability of its jet engines, a critical safety measure given the risks bird strikes pose to engines during flight.

Despite its efficiency, the chicken gun has sparked curiosity and some misunderstanding. It might surprise many that aviation authorities specify the use of real, unfrozen birds to closely mimic the conditions of bird strikes. This attention to detail ensures accurate results and the highest safety standards for aircraft.

The chicken gun is more than a quirky tool; it’s a testament to aviation engineering’s commitment to safety. By continuously testing and improving aircraft resilience, the aviation industry has significantly reduced incidents caused by bird strikes, making air travel safer for millions.